Deliveries to development

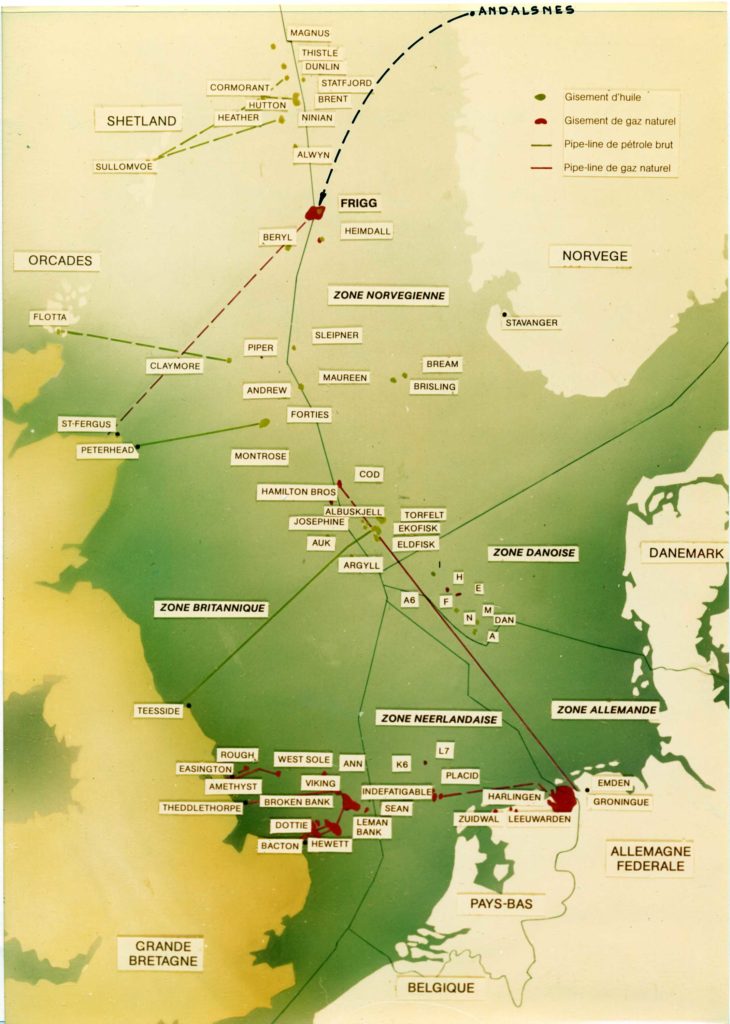

From the early 1970s, the Norwegian government was already giving weight to promoting domestic companies as suppliers to the oil industry. Conditions on establishing offices in Norway and the use of Norwegian suppliers were included in the licensing rounds which awarded acreage on the Norwegian continental shelf. While these political guidelines helped to set a more national stamp on the oil industry, the Norwegianisation process took time and did not make itself fully felt until the 1980s.

In the late 1970s, the Frigg development was one of the projects reviewed in a cost analysis of such activity on the NCS. A number of developments had found costs rising sharply compared with initial estimates, and an official inquiry – known as the Moe commission – was appointed to establish the reasons. This body submitted a wide-ranging report in 1980 on progress in the various development projects on the NCS, under the title Cost analysis on the NCS.

| Phase | NOR | FRA | UK | USA | Others |

| Phase I, britisk side 1973-1977 | 17 % | 37 % | 22 % | 16 % | 8 % |

| Phase II, norsk side 1974-1978 | 33 % | 39 % | 7 % | 13 % | 8 % |

| Phase III, compression facilities 1978-1981 | 53 % | 29 % | 6 % | 6 % | 6 % |

| Total distribution | 26 % | 37 % | 15 % | 13 % | 8 % |

Fordeling av Frigg-kontraktene pr. høsten 1978.

Tabell satt opp av Elf til Kostnadsanalysen bind 2, s.104

This report identified a number of factors which could lead to overruns.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Distribution of Frigg contracts to the autumn of 1978. The table was prepared by Elf for the Moe commission’s

report (vol 2, p 104).

One was the country responsible for the delivery, as shown in the table above. Data in the cost analysis showed that about 26 per cent of total deliveries for the Frigg development came from Norway and 37 per cent from France. While the latter accordingly accounted for the biggest share overall, it is worth noting that the Norwegian proportion increased during the development phase.

TP1 installeres, forsidebilde, historie,

TP1 installeres, forsidebilde, historie,The project was divided into phases. Phase I covered the development of the British share of the field, phase II the work on the Norwegian side, and phase III the installation of the compressors. During phase I and the first part of the second phase, Norwegian involvement was relatively modest apart from local services. One exception was the construction of the concrete gravity base structure (GBS) for the pumping platform, which was later converted to the first drilling installation (CDP1). The GBS was built in Åndalsnes by Norwegian Contractors on behalf of the French Doris group. Suppliers in Norway had an advantage in delivering this type of structure, which called for deep fjords for construction and short distances for towing. A corresponding commitment on the UK side occurred with the construction of Frigg’s TP1 platform in Scotland. The GBS for MCP-01 was built in Sweden because this country had the construction capacity needed.

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,In phase II, the Norwegian share of orders increased from 17 to 33 per cent, whilst Britain’s proportion sank from 22 to seven per cent. This was primarily because Norwegian Contractors secured the contract to design and construct the GBS and module support frame for the second treatment and compression platform (TCP2). This structure was again built at Åndalsnes. Part of the job of fabricating and hooking up the topside modules went to the Orkanger yard of France’s Spie Batignolles/Vigor. Oil Industry Services in Kristiansand became involved as a sub-contractor at the hook-up stage.

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,Companies in Norway secured more than half of all the contracts in phase III of the Frigg development, which involved positioning the compressors on TCP2. The Norwegian authorities considered it desirable that Elf placed the order for the compressor modules in Norway, since the domestic share of goods and services for the field was lower than the government expected. In a number of cases, tenders from Norwegian fabricators were uncompetitive.

Because of political pressure, companies in Norway nevertheless won a series of contracts. The largest went to a joint venture between Spie Batignolles and Vigor, with Ponticelli as piping sub-contractor. The generator and process control module was fabricated in Orkanger. By comparison, about half the total deliveries to Statfjord A derived from Norwegian companies. Ten per cent of these contracts were held to have been awarded on a non-commercial basis – in other words, bids from foreign firms were lower than those from Norway, but the latter were preferred to help build up a Norwegian supplies industry.

One purpose of the Moe commission’s analysis was to investigate whether the purchase of Norwegian goods and services was responsible for the cost increase. The study found that the rise in costs from using domestic suppliers was not especially great in relation to total expenditure. In the autumn of 1978, the development project was estimated to have cost NOK 10.5 billion. That represents an increase of NOK 7.6 billion from the 1974 forecast of NOK 2.9 billion, or more than a tripling. No less than NOK 1.2 billion of this rise related to the loss of the DP1 jacket. The additional cost of using Norwegian deliveries was put at NOK 50 million, since bids from domestic fabricators were often higher than those from foreign suppliers. According to the report, the bulk of the overruns was attributable to expensive technical solutions, often in combination with the use of consultants and weak control by the operator. Prices had also been driven up because a number of large development projects were being pursued at the same time.

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,

Leveranser til utbyggingen, økonomi og samfunn,The additional cost of using Norwegian suppliers was small by comparison with the total overruns in the Frigg development. Many had feared that political pressure to “buy Norwegian” would lead to sharp cost increases, but these worries proved misplaced. The deadline-based contract for gas deliveries meant that progress was prioritised at the expense of cost control. Delays arising from the loss of the DP1 jacket could be recovered to some extent with deliveries from Norway. The Frigg project was implemented at a time of very strong price inflation for oil industry supplies. It also proved difficult to cost the new technical solutions which were adopted.

Sources:

Moe, Johannes (ed): Kostnadsanalyse norsk kontinentalsokkel (Cost analysis for the NCS), 1981.

NOU 1999, 11: Analyse av investeringsutviklingen på kontinentalsokkelen (Analysis of investment development on the continental shelf).