The Skuld project

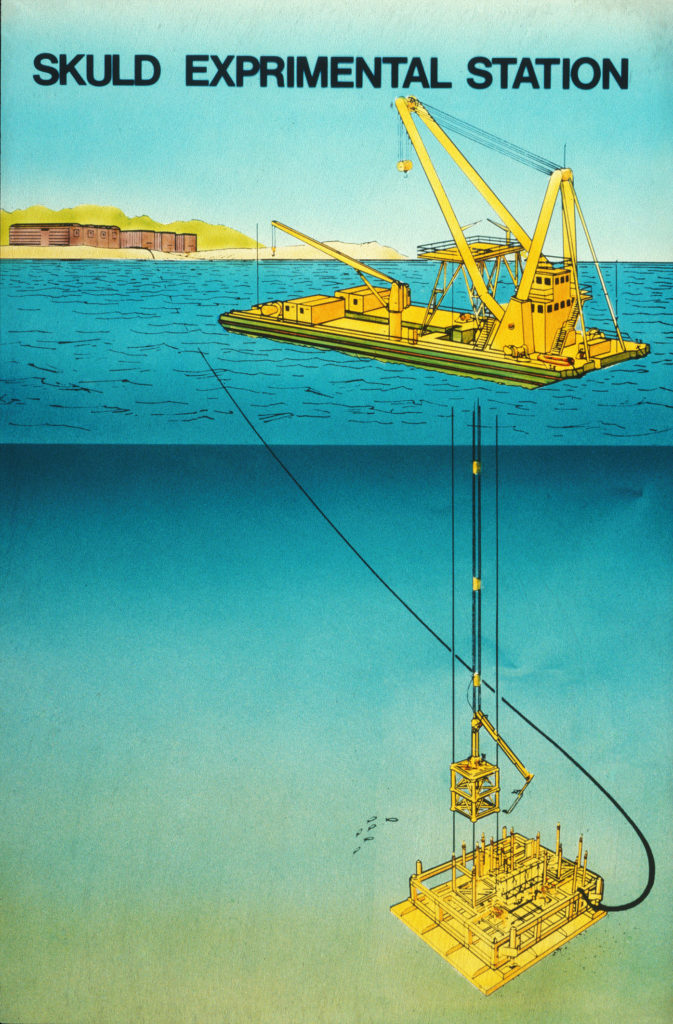

Elf responded with the Skuld project, a full-scale experiment in deepwater technology. Work began in 1980 and formed part of efforts to develop a system for remote control of subsea installations over distances of more than 20 kilometres. The project embraced a test station, which was pressurised and subject to loads similar to those that a production unit would face in the North Sea. The Skuld module was not intended to produce oil or gas, but only to serve as a research installation. Work focused on developing a simple and economic method for producing fields in deep water. Another key goal was to come up with a solution which could be installed and operated entirely without diver assistance. This represented pioneering technology development.

When Skuld was launched, Elf had some experience of both subsea production and remote control. Its first attempt was in the Gulf of Guinea off west Africa. Oil was produced on the Anguille Marine field as early as 1968 from a well which had both its Xmas tree and its safety valves placed on the seabed in 30 metres of water. The main purpose of this installation was to test remote control techniques. While the test was halted because of problems with sand intrusion, experience seemed to show that it would be possible to maintain and control a subsea installation without divers.

The next milestone for Elf where complete subsea systems were concerned was the development of North-East Grondin off Gabon in 1976-77. This project aimed to extend the producing life of the west African field while also pursuing experimental work to prepare Elf for producing oil in deep water and under difficult conditions. The water depth on North-East Grondin was 60 metres. Results from these trials were good, and gave Elf the experience needed to initiate efforts to produce subsea in the North Sea.

Skuld involved a number of large Norwegian companies and research institutes. Apart from Elf, which led the work, participants were Norsk Hydro, Statoil, Total Marin Norsk and the Sintef research foundation. Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk also played a leading role in that it was awarded the engineering studies job. The subsea template was fabricated by Bjørge Offshore at the Husøy base, while the Norwegian Hydrodynamic Laboratories (NHL) and the Norwegian Underwater Technology Centre (Nutec – now the NUI) in Bergen also participated in various areas.

Stage one in the Skuld project was the construction of a simulation station to check the reliability of a remote control system, gain greater experience with module solutions and test diverless procedures. The trials comprised assembling and system-testing of the whole production station on land. After this process proved successful, the whole Skuld station was installed in 20 metres of water during the spring of 1984 off the Nutec quay outside Bergen. The final stage involved moving the whole station one kilometre out from land and into 90 metres of water without diver assistance.

All the trials were conducted with great success. A production life of 20 years was simulated. The module concept and the diverless installation procedures functioned as planned. The remote control system proved reliable, and the simulation trials demonstrated that the concept was economically viable. This Skuld technology attracted great international attention, primarily because of the functional remote control system and the ability to assemble and operate the facility without divers.

Backed by its positive experience from Skuld, Elf initiated a new research project under the name SuperSkuld. Simulation trials with the subsea installations had demonstrated that the equipment was installable and operationally reliable to a depth of 90 metres. Through the new scheme, Elf wanted to check if it was possible to use the same hardware in waters down to 300 metres. A test off northern Norway in 1985 confirmed this.

The limitation of the Skuld concept was that it could only be used with gas wells, and not on ones producing oil. A new research project known as OilSkuld was thereby initiated. This involved two separate programmes, one in Norway called Clustoil and the other in Paris under the Saphir name. The aim was to develop two different oil production solutions, with the first intended for rough-weather areas of the North, Norwegian and Barents Seas and the other for easier climates.

SKULD prosjektet, økonomi og samfunn,

SKULD prosjektet, økonomi og samfunn,Development of East Frigg was a direct result of the Skuld project. This field lies about 18 kilometres from Frigg itself, and was commercially marginal. It was established at an early stage that a traditional platform-based development would not be profitable. However, Skuld provided a technology which allowed the field to be exploited through seabed installations. The gas was produced by two subsea stations and piped via a seabed manifold station to the TCP2 platform on Frigg.

The East Frigg installations were based on a modular design. In other words, the subsea templates supported a set of standardised equipment modules which were assembled on the seabed like building blocks. These units could be individually retrieved to the surface and replaced if necessary. Remotely operated tools were developed for this job in order to eliminate the need for diver assistance.